Why Liquidity Preferences and Distribution Waterfalls Matter to Startup Employees

Venture-backed startups often face complex financial structures as they grow and seek to reward their investors, founders, and employees. Two key elements of this financial puzzle are liquidity preferences and distribution waterfalls. For equity-compensated employees in venture-backed startups, understanding the intricacies of liquidity preferences and distribution waterfalls isn't just a matter of curiosity but something that can directly impact the value of their equity.

What are Liquidity Preferences?

Liquidity preferences are characteristics attached to each class of stock that dictate the order in which shareholders receive their share of proceeds in a liquidity event. They are essential to understand because they directly impact how much you could potentially receive from your equity, especially in an acquisition or company closure.

Here are some key points to consider about liquidity preferences:

- When They Matter: Liquidity preferences matter most when a company is acquired or goes out of business. They typically don't matter in an IPO or if you're given the opportunity to sell shares in a tender offer.

- Different Share Classes: Venture-backed startups have multiple classes of shares, each with its own set of rights and preferences. Generally, investors receive preferred stock, have a higher claim to the company's assets, and are entitled to receive their investment back before employees. While there is only one "common" share class for all employees, there may be many "preferred" share classes, each with different preferences.

- Multiple Funding Rounds: Every funding round a startup goes through creates a new preferred share class, and each round can introduce new liquidity preferences or modify existing ones. The Series A shares may be treated differently than the Series D shares, and so on. This can create a complex hierarchy of payouts, known as a distribution waterfall, which we'll discuss later.

- Participation Rights: Some preferred shareholders negotiate participation rights that allow them to receive their initial investment first (sometimes a multiple of their initial investment), plus a share of the remaining proceeds on a pro-rata basis. Essentially, these shareholders double-dip on the proceeds of a liquidity event. These participation rights may be capped, for example at three times the initial investment amount. Other preferred shareholders don't get to claim a share of the remaining proceeds (they're non-participating), but they often receive some multiple of their initial investment before common shareholders get anything.

- Cumulative vs. Non-Cumulative: Preferred stock is issued with a stated dividend yield, and cumulative preferred stock requires that any missed dividends are paid before shareholders lower in preference get anything in a liquidity event. This could have a huge impact since startups typically lack the ability to pay dividends. Fortunately, I've only seen non-cumulative preferred stock at startups, which means any missed dividends aren't paid at a later date.

- Many Other Aspects: There are many clauses and rights that can be baked into classes of preferred stock, but the most important thing to keep in mind is that as an employee and holder of common stock (or options), you're last in line to claim proceeds in a liquidity event.

What is a Distribution Waterfall?

A distribution waterfall is a mechanism used to determine how proceeds from a liquidity event are distributed among various equity and debt holders (I'll focus on equity holders in this post). The waterfall structure typically follows a sequence of "buckets," each with specific rules for distribution. Each share class' liquidity preferences are used to determine where they sit in the waterfall structure. Each bucket is filled before the next gets anything, so if there isn't enough money to go around, some buckets are left empty. Take this "simple" capital structure as an example:

- Series A (2M shares): $10M non-participating, non-cumulative preferred with a 2x preference

- Series B (3M shares): $40M participating (capped at 2x), non-cumulative preferred with a 1x preference, with preference over the Series A and common shareholders

- Common Shareholders (5M shares)

Here's how a distribution waterfall might look:

- Series B shareholders receive the first $40M. They're first in line to receive their initial investment because of their preference over other shareholders, only receive their initial investment because of the non-cumulative 1x preference. The 2x participation preference comes later.

- Series A shareholders receive the next $20M. They have preference over common shareholders, and receive two times their initial investment because of their non-cumulative 2x preference. Since the Series A shares are non-participating, this $20M is the most these shareholders will ever get.

- Series B and common shareholders receive the next $80M ($40M to Series B and $40M to common). Series B shareholders participate in proceeds alongside common shareholders until their total proceeds equals two times their initial investment. This distribution is pro-rata, so if only $30M is left to distribute, Series B and common would receive $15M each. This is where the 2x participation preference comes in.

- Finally, common shareholders receive all remaining proceeds. Since the Series A and B shareholders filled their buckets, they don't participate in any of this upside.

Therefore, Series A shareholders will receive $20M, Series B shareholders will receive $80M, and common shareholders will receive $40M plus all additional proceeds.

Why Don't Waterfalls Seem to Apply to Big Acquisitions?

In big acquisitions, the scenario above where preferred shareholders are capped on their upside never seems to play out. Instead, everyone participates evenly in the proceeds, which contradicts the idea of liquidity preferences. The reason for this is that preferred shareholders of startups almost always have convertibility rights attached to their shares. Although the discussion up to this point has focused on the ways common stock is "worse" than preferred stock, the example above highlights a key reason why convertibility clauses are highly sought after.

Notice in the above example how the Series A shareholders can only get $20M at most, and the Series B shareholders can get $80M at most, no matter how big the liquidity event is. If there's a $1B liquidity event, common shareholders would get all of the remaining $900M.

Convertibility allows preferred shareholders to convert their preferred stock to common stock so they can also enjoy all of the upside. The tradeoff is relinquishing all liquidity preferences and priority of having preferred stock, which is why conversions most often happen when a liquidity event occurs and preferred shareholders can see whether converting to common will give them a bigger profit over keeping their preferred shares. This way, preferred shareholders are able to recover more in a subpar exit and still reap all of the upside in a massive exit.

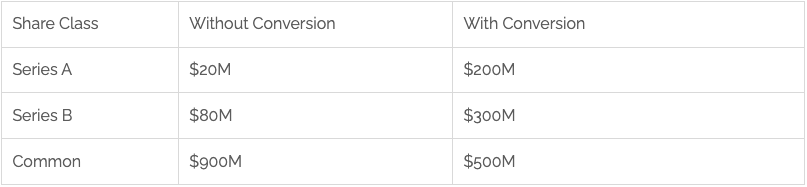

Continuing the $1B liquidity event example, assume the Series A and B shares have a 1:1 conversion ratio (one preferred share becomes one common share). If all shareholders convert to common, the $1B is distributed proportionally among 10M shares (2M Series A, 3M Series B, and 5M common). Therefore, Series A shareholders now get $200M (20% of the total), Series B shareholders get $300M (30% of the total), and common shareholders get $500M (50% of the total). The waterfall distribution becomes completely irrelevant with big enough acquisitions where everyone converts to common.

Distribution Waterfalls Hurt Common Shareholders in Smaller Acquisitions

On the other hand, a $100M acquisition would result in one of the following scenarios:

A little bit of game theory shows it's in the investors' best interests to not convert in this case. Converting to common can never leave a Series A shareholder better off, and Series B holders converting will only leave them worse off. Therefore, Series A gets $20M, Series B gets $60M, and common shareholders get $20M. Remember that common shareholders are just along for the ride, and they can’t force the Series A and B shareholders to convert to common.

This is a clear example of how liquidity preferences and distribution waterfalls can hurt common shareholders. If investor stock was treated the same as employee stock, everyone would get the same price per share for their stock, $10. However, because of liquidity preferences and the distribution waterfall, Series A investors receive $10/share, Series B investors get $20/share, and common shareholders get $4/share. That's how founders and employees can walk away from a several hundred million dollar acquisition with close to nothing.

When Waterfalls Don't Apply to IPOs: Mandatory Conversion

IPOs are a little different because in order for preferred shareholders to sell their stock at the IPO or afterward in the public markets, they usually must convert their preferred stock to common. If everyone converts their shares to common, the waterfall distribution is irrelevant. This is why we rarely, if ever, hear about this concept when a company goes public. It's still possible though - if the IPO isn't large enough or the share price isn't high enough, preferred shareholders may not be forced to convert.

With IPOs often being seen as the ultimate goal for startups and their employees, and given the sheer complexity of distribution waterfalls in low and mid-priced acquisitions, it's no surprise that liquidity preferences and distribution waterfalls aren't discussed by employees and advisors too much.

However, for equity-compensated employees in venture-backed startups, liquidity preferences and distribution waterfalls are pivotal factors that can significantly impact your financial future, and understanding how they can impact you is critical as you make decisions with your pre-exit equity.

Categories

Have questions about this post?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod temor.